As I said in my overview on what is a verse in a song, a song’s verse might be the second most important element in a song, next to the chorus. Typically in songwriting, at least in most popular music, the ultimate goal of a verse is to support and make the chorus of the song bigger and better.

Let’s talk about how to write a verse for a song.

How to Write a Verse for a Song

While certainly not mandatory, oftentimes it’s better to write a verse if you’ve already decided on a chorus for a song.

There are a few reasons why I recommend doing it this way:

The Chorus is King

Typically a song revolves around its chorus. This is the that most important element of a song which separates a good one from a forgettable one.

With that in mind, there’s much more incentive in establishing a chorus first so that you can be sure that it’s a great song worth building out from the start.

Put another way, if your main concern is writing a great song, then why waste your time writing a verse until you know that the main draw of the song (the chorus) is solid.

Lower Expectations

The stakes are much lower when you’re writing a verse for a song as opposed to its chorus. By definition in terms of songwriting, a verse shouldn’t be as hooky or memorable as the chorus.

As I talked about in the aforementioned tutorial defining what a verse in a song is, there are a lot of songs which are so identifiable by their choruses that most people can’t name the song until that chorus hits. That makes me think of an old Simpsons clip which always makes me chuckle:

Because the stakes are lower for the verse, it’s easier to write one after you’ve established what your chorus is going to be.

Filling in the Gaps

From a practical standpoint, once you’ve got your chorus, you have a sense of what the song is about musically and lyrically. You know the energy level at that peak of the song which is the chorus.

All of this helps give you your bearings so you can start working backwards and setting up the next area of the song.

Let me clarify here that you absolutely don’t need to begin with a chorus. If you come up with a melody but it doesn’t feel like it’s catchy enough to be a chorus, this can make for a good idea for a verse to use later with another song.

It’s good to have a means of recording ideas on the fly; a voice memo app on your phone will do just fine so that you can hum or sing an idea as you get one whenever inspiration hits. The more songs you write, the more often these ideas will come to you.

I like to categorize my ideas as a “verse”, “prechorus”, “chorus” idea, etc.

Now let’s get back to how to write a verse for a song.

Avoid at Least One Chord You Use in Your Chorus

Here we’re kind of working backwards from an idea to benefit the chorus, but the point is to be aware of all of the chords you use in your chorus.

Using a new chord which the listener hasn’t heard yet for the first time midway through a song (like when you get to a chorus) is refreshing to the listener’s ear.

With that in mind, make it a point to not use at least one of those chords ahead of time, including in your verse.

Let’s say your song is in the key of “E”, and let’s say the chord progression of your chorus is E, B, C#m, and A. This is a very popular chord progression in popular music, also known as the 1-5-6-4.

If that’s the chorus progression, for the verse you might withhold that minor chord, the minor 6th or in this case the C#m. Instead in the verse you might just use a simpler E, B, A, A progression (the 1-5-4-4, another popular progression).

This will make that change during the chorus more impactful.

Take Jason Isbell’s rocker “Cumberland Gap” as a song which doesn’t give you two very important chords until the chorus.

The intro and verses keep repeating the same Bm to A rhythm (with a couple quick teases after a couple of measures). This minor-based, simple, and repetitive progression teases a change on that chorus. It builds the tension and anxiousness which matches the tension in the lyrics of feeling your hometown strangling you while you yearn for something bigger:

That tension gets released once that chorus hits and we finally go to the two most important major chords here of G and D. It feels like a triumph despite the explosiveness of the lyric “maybe the Cumberland Gap will swallow you whole”.

Outside of the A chord, the verse and chorus use two almost completely different sets of chords.

If you can do this while keeping that transition natural sounding like this song executes perfectly, you’ll have a wholly refreshing change between the two parts in your song, keeping it from ever stagnating.

Use a More Complex Melody

The chorus is perfect for the catchiest which is oftentimes the simplest melody in your song. You’ve likely heard of the term “hook” for a catchy part of a song. The purpose of the hook is to draw in the listener.

A simpler melody is easier to remember, repeat, and get stuck in your listener’s head.

This is why oftentimes we save our simplest, catchiest melody which is made up of less notes (and more emphasis or time held on each note) for the chorus.

To create a nice contrast, we can use a more complex melody in our verse. We can fit and comparatively crowd our verse with more lyrics and less space between each word.

Then, when that chorus hits, the song gets bigger and opens up musically compared to the preceding part.

This is certainly the case with Adele’s “Rolling in the Deep”. Compared to the chorus, the verses use a much more complex melody. It’s certainly not a throwaway melody in this case as it operates in a very memorable structure in terms of rhythm, timing, and notes moving up and down the scale.

It works well to build that tension once again to lead into the chorus when we’re waiting for her to let that first held out word “allllll” soar:

You always need somewhere to go in the flow of songwriting, and you always need to be able to get bigger in that chorus, so plan for that transition with your verse.

Use a More Forgettable Melody

This is an extension of that last point, but it’s so useful to keep in mind.

The catchier that verse is, the less impactful that chorus is going to be. You always want your listener to know definitively the second your song’s chorus hits.

I’ve used this song as an example before, but Carly Rae Jepson’s ubiquitous “Call Me Maybe” fits the bill here.

The verses are sung in a lower register with less power behind the voice, and musically everything is tamped down. There’s a certain level of build, though it mostly comes on at the tail end of the prechorus to launch into that famed chorus:

Some songs’ choruses are just so huge that the verses really are an afterthought. That doesn’t mean that they’re not doing their job; it’s just much more subtle as most people don’t think about why that chorus feels as good as it does. It’s what the verse “gives up” to make that chorus larger than life like this example.

Some songwriters intentionally write a more throwaway melody for the verse in order to make that chorus hit harder. I teach this technique myself in my complete guide on how to write a song, deeming it “garbage to gold”.

This sets up your listener to have certain expectations in order to surprise them and get a bigger payoff on that chorus.

Use Verse Lyrics to Create Evidence for the Chorus

Just like musically, your main theme of your song lyrically should be kept for the chorus. This is the message you want to drill into your listener’s heads.

And once again, lyrically your verse should serve to make that chorus stronger.

In the case of lyrics, we can use our verses to provide evidence for the main argument that we’re making in that chorus.

In other words, this means using the lyrics to provide more context for that chorus.

I used this example in my overview on what is a chorus in a song, but Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” is masterful at using its verses to provide context for the chorus and making it more impactful.

Specifically the first verse (and prechorus) paints the picture of this woman that everyone wants but also a woman to be wary of. We can tell its not a happily ever after when we learn that she has set her sights on the narrator of the song and there’s more to the story.

The verse builds our anticipation and need to know what we can feel the narrator is dancing around. It does an excellent job so that we’re at the edge of our seats when the chorus hits and drops the bombshell of what the song is REALLY about:

Again this is just one excellent example of storytelling and specifically pacing, using the verse to set up a monster chorus both musically and lyrically.

Lower Energy and Register

Lastly, using that chorus as a guide gives us more perspective as to how to manage the energy of our song. We know that we’re peaking with that chorus, so we know how much lower to go in that verse.

In the same vein, we can plan to sing lower notes and with less intensity in the verse as compared to the chorus. Songwriting again is all about dynamics and contrasting sections to keep your listener engaged top to bottom, beginning to end.

Similar to the transition from a forgettable to a huge hooky melody (garbage to gold), we can subvert the listener’s expectations by singing in a lower register on that verse only to push to a higher register with more emotion behind those notes on the chorus to really capture their attention.

How Long Should a Verse and Chorus Be

I get asked how long should a verse and chorus be.

There’s no perfect length for a verse or a chorus in a song, not a one-size-fits-all approach, at least.

Rather than saying it should be “this number of seconds” or “4 bars”, it’s a matter of what feels right.

In the case of a verse, you have to find that sweet spot where you’ve built enough anticipation in the listener for a big change without putting it off too long and losing their interest.

In the case of a chorus, you have to find that length right before it becomes too much and the chorus loses its luster.

How to Write a Verse From a Chorus

We just talked about how to write a verse from a chorus, and again why it’s easier than writing a verse from scratch.

You know that most of the time, the energy level needs to come down from that chorus. There are exceptions to this; some songs use the chorus to take a breath to slow things down after a chaotic, faster, or just louder verse.

The point is you have a good starting point from the chorus, so you have a better idea of how to offer up something different in that verse like we talked about above.

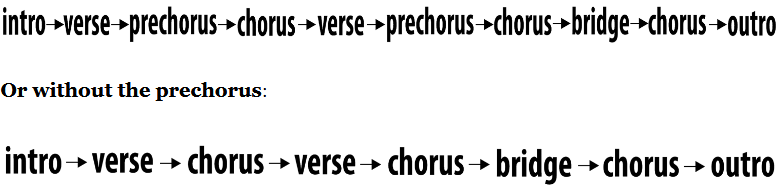

Verse Chorus Structure

The verse chorus structure is as old as time and it has always worked because it keeps the listener engaged throughout.

There are some variations on it, like the example below.

While some songs use additional elements like an intro or a pre-chorus or bridge, the verse chorus structure is the one constant in virtually all popular music.

How Many Verses Does a Song Have

Most songs have two verses. There are certainly exceptions to this; often times if there’s a third verse it comes after the second chorus and almost acts as a bridge.

If this verse is the same as the first two then typically we refer to it as a third verse. If the section after the second chorus is unique we typically refer to it as a bridge.

The two verse structure goes along with the verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus which is one of the most common songwriting structures in popular music.

It keeps the song at a tight length, as well, so that you don’t risk losing the listener’s interest.

Example of a Verse in a Song

I’ve just given several examples of a verse in a song.

Here is another example of a verse in a song (or 5) taken from YouTube, with each set to begin on the verse:

Justin Timberlake – “Mirrors” Verse: